- Home

- Stan Marshall

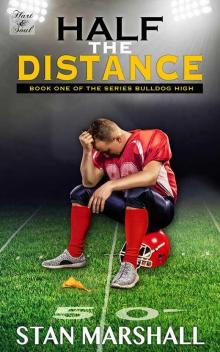

Half the Distance

Half the Distance Read online

Warning: The unauthorized reproduction or distribution of this copyrighted work is illegal. No part of this book may be scanned, uploaded or distributed via the Internet or any other means, electronic or print, without the publisher’s permission. Criminal copyright infringement, including infringement without monetary gain, is investigated by the FBI and is punishable by up to 5 years in federal prison and a fine of $250,000 (http://www.fbi.gov/ipr/).

Published by The Hartwood Publishing Group, LLC,

Hartwood Publishing, Phoenix, Arizona

www.hartwoodpublishing.com

Half the Distance

Copyright © 2017 by Stan Marshall

Digital Release: January 2017

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This book is a work of fiction. The names, characters, places, and incidents are products of the writer’s imagination, or have been used fictitiously and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to persons, living or dead, actual events, locales, or organizations is entirely coincidental.

Half the Distance by Stan Marshall

When seventeen-year-old Todd Nelson—preacher’s kid, football player, and all-around good guy—moves from big city Houston to a small Texas town, he must leave everything he loves behind—his teammates, good friends, and his cheerleader girlfriend. As with every other teenager in the world, he didn’t have much say in the matter. His dad even had the nerve to say, “I think this move will be good for all of us.”

In what universe?

For Todd, adjustment to a new school in a new town is hard enough, but just as his football skills begin to gain him acceptance in the new school, the roof caves in. He is blamed for his new team’s loss in the championship game. With high school football ranking two notches above God and country in rural Texas, Todd becomes a pariah, not only to his schoolmates but to the whole town.

As his life continues to deteriorate, he focuses on the injustice of being held responsible for something he doesn’t think is his fault. He’s always tried to do the right thing, and look where that got him—paying for a mistake someone else made. If the devil was looking to make a deal, Todd was just about ready to sign on the dotted line.

Todd finds himself battling not only against flesh and blood, but his own inner demons as well. Can he find the courage to fight when his whole world is being ripped apart? And is courage alone enough?

Chapter One

Old Yeller, the team bus, clocked along Highway 71 on the sixty-five-mile trip from Arnett Stadium in Austin back into the bowels of my own heinous personal version of hell. I didn’t know if the French Foreign Legion or the Namibian Mercenary Forces still existed, so suicide loomed larger and larger as my best option.

The hum of the road filled my ears, and my hands covered my eyes. If anyone ever needed a time-traveling DeLorean, it was me.

I’d set the dials back six weeks, switch on the ol’ flux capacitor, and kick her up to eighty-eight miles per hour. Boom! I’d be back in Houston where I belonged. Back with Ashley, my smoking-hot cheerleader girlfriend, back hanging with my Heritage Park High football buddies, most of whom I’d known since grade school. I wanted my old comfortable life back.

But real life is just that—real—and time machines aren’t. Houston was then, and this is now.

My old life was good—no, it was great. Then, one Sunday evening at the dinner table, Dad announced his “exciting” news. Between pouring himself a glass of iced tea and buttering his roll, he announced, “I’ve resigned my pastorate at Abundant Mercy Church here in Houston and accepted a new pastorate in a quiet, less hectic community in the Texas hill country.”

Little did I know a journey into my own personal abyss was about to begin.

I tried to protest. “But Dad, it’s the middle of football season.” It didn’t matter. “I’ll be a senior next year and captain of the team.” No big deal.

“Son, you’ll make new friends and have a new team. It will be exciting.”

“Exciting” was not the word I would have chosen to describe Dad’s news. The issue was settled. The king had spoken. And me? I was, as are all teenagers, powerless.

This one thing is universally true: parents are clueless, even the good ones. They act like changing schools, neighborhoods, and towns is no big deal. If you complain that all your friends are at your old school, they say, “You’ll make new friends.” As if you were replacing Friends 1.0 with the latest 2.0 version.

It didn’t matter to them that it was the middle of football season and the team needed me, or that the coach said I was a shoo-in for All State.

To Dad, it was only football, and not a matter of life and death. No biggie. “Besides,” he said, “it’s not like we’re moving to Tibet or Afghanistan.” But to me, it might as well have been.

When you’re the newbie someplace, you have to start everything all over. You go back to dead zero. Everyone and everything is strange. Strange school, strange coaches, and strange people. Then, even when you get to know them, what if you don’t like them? What if they don’t like you? Parents don’t give the stuff that matters to a kid a second thought.

Dad’s side of the conversation was short and to the point. “We’re going. But don’t worry, son. Everything will work out fine. You’ll see.”

The king had spoken and his subjects must obey.

Chapter Two

BRANARD, TEXAS

Population: 21,754

Home of the Fighting Bulldogs

To say football is king, in small-town Texas, is a gross understatement. Oh sure, there are other places in the country where high school football is popular, or even held in high regard, but in the small towns all across this state, Friday nights are holy and high school football is a religion.

This phenomenon isn’t limited to game days, or even football season. It’s a three-hundred-sixty-five-day-a-year affair, and to fully appreciate how high school football affects these communities, you must experience it firsthand.

On football Friday nights, small town main streets empty and all commerce ceases. Even the Super Savemarts, out on the highway bypasses, pare down to a skeleton crew. Towns of 10,000 people boast high school stadiums with 20,000 or more seats and amenities that rival most university facilities. Every game is an overflow sellout.

For out-of-town games, caravans of packed pickups and cars begin to roll out of town at noon for a seven-thirty-p.m. kickoff an hour’s drive away. As anyone can tell you, “You’ve got to show up early to get a decent seat.”

At my old school in Houston, football was the most popular sport and a significant part of life. It just didn’t rank three notches above a viable heartbeat as it would in Smallville.

When we moved from Houston to Branard, Texas with its 21,754 hayseed citizens in early October, I believed my life was over. I’ve loved football for as long as I can remember and have played the game since Youth League when I was six, but football did not consume me twenty-four hours a day, all year long.

By the time we moved away, halfway through the season my junior year, Houston area sportswriters wrote, “Heritage Park’s Todd Nelson is a viable candidate for the Houston’s Athlete of the Year.” I had a cheerleader girlfriend and tons of buds. Six weeks ago, life was good. It was like The Stone Dock’s song said, “I had heaven in my hand and the devil didn’t even know my name.”

Life in Branard started out a little better than I anticipated. Within three weeks of the transfer, the new coach promoted me to the starting lineup. I started at right defensive end in the Branard Bulldogs’ last three regular district games and switche

d to left defensive end, my natural position, for the district playoff against the Yarell Tigers and the quarterfinals against the Pratt Panthers. We won both games in a walk.

Because I filled a need on their beloved football team, some folks around Branard stopped treating me like an alien from the Zulak Galaxy. It looked like life just might work out okay after all. Silly me. Had I known what the future held, I would have quit football and joined synchronized swimming.

On the third Saturday in October, we played West Cleary in the state semifinals. I made eight tackles, three for losses, rang up two sacks, and forced a fumble. Under ordinary circumstances, the Branard Daily Sun’s Sunday morning headlines would have read, BULLDOG’S NEWEST ADDITION DEVASTATES WEST CLEARY’S OFFENSIVE IN 17-13 VICTORY.

“Under normal circumstances,” and “would have,” were the operative phrases. Instead, the headline read, NEWCOMER BLUNDERS AWAY BULLDOGS’ HOPE OF STATE CHAMPIONSHIP.

Newcomer? That would be me.

And since in Branard Friday-night high school football isn’t an event, but a way of life, losing is not tolerated. Those blamed are likely to be burned at the stake.

The Branard Daily Sun story by Doyle Helms read:

Expectations were high as the Bulldogs took the field last night. Quarterback Lance Brighton needed only one more victory to break the Texas High School football’s longest-standing record, most consecutive wins for a starting quarterback.

Governor Patterson, US Representative Hanover, and most of Branard’s citizenry made the trip to Austin’s Arnett Stadium to cheer their beloved Bulldogs on to victory. Coach Newcomb all but guaranteed a victory. And why not? In the season’s second non-district game, his boys had beaten those same West Cleary Lions 38-10.

The first half was all Branard. Lance Brighton threw for 210 yards and two touchdowns. Officials called back another touchdown pass on a ticky-tack push-to-the-back penalty. On the ground, Ricky Witt ran for 54 yards and Danny Garcia contributed 22 more. With a 17-6 lead going into the fourth quarter, the game appeared to be well in hand. However, the Lions ran a Paul Delhome punt back 88 yards for a TD. With the extra point, the score was Bulldogs 17-Lions 13.

With 31 seconds left on the clock and Branard still leading by 4, West Cleary had the ball, fourth and four on the Bulldogs’ 11. If the defense could hold the Lions to three yards or less, Branard High would be in the State Championship game.

Bulldog right defensive end, Randy Unsel, stopped the Lion’s running back for a loss on the play. It was mayhem in the stands and elation on the field. With less than thirty seconds on the clock and only one Lion time-out left, the Bulldogs were on their way to the championship game and Lance Brighton to being the winningest quarterback in Texas high school history.

Then the PA announcer quieted Bulldog fans in an instant with the words, “Ladies and gentlemen, there is a flag on the field.” Hearts stopped as all Branard prayed, “Not against us, please, dear Lord, don’t let the penalty be against us.”

The referee flagged Todd Nelson, #83, the Bulldog’s left defensive end, for holding. Nelson not only grabbed the jersey of a West Cleary lineman, he shattered the hearts of 21,754 Branardians. The half-the-distance penalty gave the Lions a first down on the Bulldog five-yard-line. Power Left Toss, and it was second and goal at the one. Time-out. On the next play, Lion quarterback Phil Oliver sneaked into the end zone at the gun. Game over. Lions 19, Bulldogs 17. Tears all around.

Chapter Three

When I realized what had happened, I was angry. I would have expected frustration, embarrassment, or maybe depression and disappointment, but the anger—bordering on rage—was a surprise. I’d been an even-tempered guy my entire life. I tried to live by what Dad called factor evaluation. Before reacting to something, look at the whole picture. See where this one thing fits into the scope of things. Where does it rank compared to everything else in your life?

My dad taught me that once you see a thing in comparison to the millions of events you would experience in your lifetime, it’d be all but impossible to get angry with the clerk who got your order wrong, or at the school administrator who made you wait outside his office for half an hour. Dad says most of the things we get upset over aren’t worth the time and energy of being mad. It sounded reasonable, but sometimes reason has nothing to do with it.

The PA announcer’s voice rattled in my ears but never made the trip to my brain. I did hear the groans and gasps from the east stands loud and clear. A half-blink later—nothing but hollow silence, the dead quiet before the storm.

A booming voice cracked through the quiet. “Lions’ ball, first and goal at the five.” That, I heard.

“What? What happened?” I asked the people around me.

From somewhere over my shoulder came the answer. “You were called for holding, you ignorant toad.” The words cut straight through to my soul. The quiet gave way to deafening roars of jeers and boos, and they were all, unmistakably, aimed at me.

Before I could gather my wits, the game was over, and the coaches steered us toward the locker room. As we passed by the rail that separated the fans from the field, I was pelted with cups, most half full of ice. One cup, full of ice and soda, hit me on the neck and spilled down my back. The cold stream of sticky liquid ran down my spine. I shivered. Where was Invisoman’s cloaking ring when you needed it? I prayed for a lightning bolt to strike me dead, but as it turned out, God must be a Bulldog fan too.

I’m always expected to be clean-cut and to stay out of trouble. More is expected of me than other guys, because my dad isn’t only my father, he’s also my pastor, not an easy situation for either of us.

I’m supposed to turn the other cheek when I’m cussed or trashed. Of course, I do have one advantage. Ever since a growth spurt in the fifth grade, I’ve been bigger and stronger than other kids my age. I’m sure some people still called me names and made fun of me, they just didn’t say it to my face. And to tell the truth, I didn’t much care one way or the other even before I grew.

My dad must have said it a hundred times. “For a person to hurt your feelings, you must care what they think and believe their opinion is valid.”

I always tried my best to keep that in mind, but this time, things were different. I did care. I’d let the team and the school down. When I transferred from Houston, Coach Newcomb fought hard for an exemption to the in-state transfer rule that required student athletes to sit out a year of sports eligibility. He even convinced the school board to approve four thousand dollars for legal fees and such. Coach put in a lot of time and effort to get the exemption, and when it came through, everyone in town congratulated me. How could I look them in the eye? Foolish or not, it did matter what other people thought. I cared what people would say. And believe me, they would say plenty.

Inside the dressing room, locker doors slammed and equipment rattled as the guys flung helmets and pads against the lockers and onto the floor. Instead of rebel yells and happy chatter, over the gurgles of the whirlpools and the hiss of the showers came angry curses and hateful insults hurled directly at me. I sought a reprieve in the shower by running a full-force stream of cold water from the shower over my head. The water filled my ears and muted all but the most piercing sounds. With my teammates’ ire muffled to a far-off drone, I longed for the sweet silence of nothingness.

I closed my eyes. Dear God, don’t let this be real. Let it be a dream.

But when I opened them again, I knew it was real.

From the time the PA announced the penalty until I got off the bus in Branard, almost four hours later, the only person to speak to me was Bill Harrington, the defensive line coach. As we left the locker room to board the bus, he slapped my shoulder and said, “Bad break, kid. It shouldn’t have come down to that one play. There were at least a dozen mistakes that lost us the game.”

Maybe it shouldn’t have come down to that play, but it did. No one in Branard would remember Lance’s three interceptions, Sean’s fumble on our own four-yard lin

e in the third quarter, or Keaton’s clipping penalty that nullified Dru Witt’s touchdown run in the third. By the time we got back to Branard, everyone in town had forgotten everything except that one play and the one player they held responsible for their team’s defeat. Me.

Branard was a small town, and Branardians were, in my experience, mostly unsophisticated country folk with 1950s morals and mores, but as is so often the case, mores trump morals when there’s blame to be placed. Country folk were supposed to be simple friendly people with deep religious and moral convictions, but when we moved to Branard two months ago, we found that southern hospitality, friendliness, and acceptance were all reserved for the locals. Because of football, the kids at school had begun to accept me as just one of the guys. Now this.

»»•««

I got home at straight-up two a.m. Mom slept on the couch covered with her favorite blanket, and Dad was laid back in his recliner snoring like a straight-piped 1200cc Harley-Davidson. They would have both made the trip to Austin to see me play, but Dad’s board of deacons called an emergency meeting and Mom wasn’t feeling well. No doubt they had followed the game on the radio and listened in horror to the news of their oldest son’s athletic and social demise.

I crept to my room, relieved I didn’t have to talk about the night’s debacle but disappointed they couldn’t stay awake, knowing how upset I would be. I told myself things would be better in the light of day, but I knew it was a lie. Things would not be better.

I tried to sleep but couldn’t. That one wretched play reran in my head like an endless blooper loop. I drifted off a couple of times, once around six for half an hour and again between eight-thirty and nine after I heard the family leave for church.

Dad was a stickler when it came to Sunday school and church. No matter how late I got in Saturday night, or Sunday morning, he expected me to show up at nine-thirty sharp—neat, clean, and in a pleasant mood. I appreciated the reprieve. I would have to say that Dad was always strict, but he did have a considerate side. The move to Branard aside, as dads go, mine wasn’t that bad.

Half the Distance

Half the Distance