- Home

- Stan Marshall

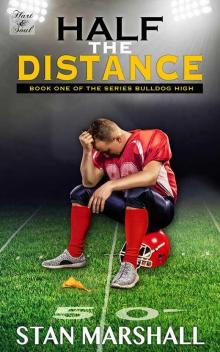

Half the Distance Page 3

Half the Distance Read online

Page 3

“Have you been behaving yourself?”

“Uh, yes, sir,” Law answered and sheepishly grinned at me.

I’d definitely ask Law about that one later.

The officer turned his attention to Jeremy and Dewayne. “Come on. You’re supposed to be big strong football players. You ought…” He stopped midsentence and slowly turned his gaze back to me.

It was in his eyes—the disappointment, the disdain.

“Nelson?” He spoke the name slowly. “Are you Todd Nelson, the boy who cost the Bulldogs the championship?”

I didn’t answer. I clinched my jaw, lowered my head, and quickly walked to the house. I intended to fling the door open, step inside and slam it behind me in a grand dramatic gesture. Instead, when I tried to fling the door open, I found it locked. We never locked the door before bedtime.

To make things worse, I had forgotten to bring my keys. I glanced back over my shoulder to be sure Jeremy and Dewayne weren’t watching. Nothing kills a dramatic exit like having to ring the doorbell and wait for your mommy to come let you in.

»»•««

Mom and Dad were, as always, calm and supportive. That’s the folks. Mom, the supportive one, and Dad, always the calm one. Mom always acted as though I were a perfect angel, and Dad never got upset at anything. I think if I told Dad I had set fire to the church, he would calmly ask me to sit down so we could discuss what it was that caused me to behave that way.

All things considered, I didn’t have too much of a gripe coming, considering how much better I had it than most kids my age. Take Law for example. His father was in prison, and his mom worked as a housekeeper for a rich family living in Monterey Heights—or as some called it, Money Hill.

Mom opened the door and smiled her everything-will-be-all-right mom smile. Dad stood at the window silently engrossed with the show out front. Law and I slipped by them and hid ourselves away in my room playing Starkiller IV on the BotBox until almost five.

I walked Law to the door. Dad was still at the front window watching the show outside, and Mom was rattling around in the kitchen. As we reached the door, Mom stuck her head into the living room and asked Law if he wanted to stay for dinner.

“No, thank you, Mrs. Nelson. I have to pick up my mom. She had to work today. Mrs. Kitzman needed her to get their house ready for her sister and family. Her sister’s husband ran off with the redheaded widow who used to work at the post office, so Mrs. K’s sister and her two kids are going to be staying with them for a while.”

There are no secrets in Branard. A mouse sneezes two miles north of town, and two seconds later, a cat on the south side says, “God bless you.”

Mom frowned at the gossip but said she would see if she could get some of the ladies from church to supply some meals for them.

I told her, “Mom, the Kitzmans are mega-rich. They can afford to eat out every night.”

“Just because someone has money, it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be willing to pitch in and help when they need it.” That was my mom, the kindest, most unselfish person I knew.

I tried to sneak back into my room before my dad finished studying the crime scene. I wanted to ask him about putting up a floodlight on the eave of the house, aimed toward my truck, but I didn’t feel much like talking. I’d ask some other time.

Chapter Four

Monday morning was sheer misery. I got to school early so I could park in the front lot on Patten Street. Patten was always busy with traffic and the lot sat in clear view of the admin office. My Ford truck might have been twelve years old, but I kept it in tip-top shape and didn’t want another attempt at a custom paint job if I could help it.

One week ago, the Alumni Booster Club voted me Bulldog of the Week. Among the reward were a free haircut at Kroler’s Barber Shop, a dozen free donuts at Mama Dawson’s Bake Shop, and a free oil change at the Super Lube. Everywhere I went, people had said, “Nice job, Todd,” or, “Way to go, Todd.” People I didn’t even know were slapping me on the back and saying how proud they were I had moved to Branard.

The day began as every other Monday morning during football season. The team met for “skull practice” in the athletic field house, behind the main building. We watched the films and reviewed our performance from the past Friday night’s game.

The only positive thing about going over the film the Monday after the loss to West Cleary was that I could finally put to bed the question of whether or not I actually held on that crucial play. If the film showed I didn’t hold, I would be off the hook, and everybody could start ragging on some poor insurance salesman or butcher who referees high school football for a hundred dollars a game so he can send his son to summer camp or buy his daughter braces.

If it showed I did commit the foul, I would at least be free from the nagging feeling I was being unjustly accused and persecuted. It wouldn’t help the embarrassment or slow the snide remarks and nasty looks, but it would give me chance to apologize to the coaches and the team. Maybe then, people would at least start to lighten up a bit.

There was a note on the field-house door. It read,

Skull practice cancelled due to the end of the season. Spring practice begins May 6, and the spring scrimmage game will be on May 27. Basketball practice today in Gym #2 at 2:25 PM.

At Branard, if a student went out for one sport, they had to go out for them all. That way, seventh period PE could be part of athletics practice. I suspect it wasn’t exactly legal. Whatever the case, I was terrible at basketball and hated the daily running drills b-ball practice entailed.

I steered clear of people all morning, careful not to make eye contact. No use poking a mad sleeping bulldog. I got a lot of contemptuous looks but no verbal rebukes to my face. Those would come later when I showed up at the gym for basketball practice. The football team would be there as well as the coaches, and there were always a dozen or so diehard fans in the bleachers. Oh joy.

I’d asked my dad if I could stay home for a day or two. He gave no sympathy and showed no mercy.

He said, “This is how things go sometimes. You have to take the good with the bad and move on.” He made an abbreviated fist pump and said, “Just remember, nobody can affect your value as a person but you. A man’s worth is in his soul and in his character, not in how other people see him.”

My head agreed, but my heart and stomach didn’t see it that way. After all, I’m a teenager with teenage anxieties and self-doubts, not a battle-hardened marine.

»»•««

I changed into my basketball practice uniform as fast as I could. I wanted a chance to talk to Coach Newcomb before practice actually started. He was not only the head football coach but the assistant basketball coach as well. All of the other coaches had to coach at least four of the five sports, football, basketball, baseball, soccer, and track. Newcomb only coached two, an indication of just how highly esteemed Branardians held their high school football.

Coach was standing outside his office door when I approached. “Hey, Coach, when are we going to get a chance to go over Saturday’s game video?”

He didn’t answer but shot me a glance that said, “How dare such a lowly maggot as you address his royal highness as though he deserved a royal audience?”

I was a little shocked but mostly angry. I had never before been so casually ignored by a coach or teacher. I stepped closer and asked again, louder but careful not to project a disrespectful tone. “Come on, Coach, it won’t take but a minute.”

“Get out of my face, boy,” he growled as he tried to shoulder his way past me. I held my ground long enough to let him know he didn’t have what it took to move me, and then I stepped aside.

Everyone treated me like either a malicious virus or their personal punching bag all practice long. Players passed the ball just out of my reach and fouled me at every turn, while the coaches turned a blind eye. None of the coaches bothered to speak to me, unless it was to chew me out for some minor misstep. Even Coach Harrington ignored me. And he was on

e of the good guys.

I couldn’t take much more. It was beginning to get to me. I had a near uncontrollable urge to grab every one of them by the scruff of the neck, shake them, and yell, “Get over it! It was a game, you idiots! It was just a dumb old football game, nothing else! I didn’t burn down a nursery school with all the kids locked up inside, or poison the town water supply with arsenic!”

After practice, I caught up with Coach Newcomb. I sucked in a long cleansing breath and let it out slowly. I calmly asked, “Coach, please. Could I look at the game film from Saturday? I think the back judge blew that call.”

He started shaking his head No before I finished asking.

“Coach, I need to see that tape. Everybody is treating me like a rabid skunk, and I don’t think it was even me who held.”

“You know it was you, Nelson.” He put a heavy emphasis on the know. “Everybody knows. Let it go.” He wheeled a one-eighty on the balls of his feet and regally walked out to his new midnight blue Cadillac Escalade, a “loaner” from a grateful alum.

Murder was wrong. I got that, but I was beginning to consider there might be an exception.

I jogged out to the parking lot and waited for Law. We had steered clear of one another during basketball practice. I didn’t want to make him feel like he had to take sides. I knew if he hung around me, he’d be branded a traitor by the other guys on the team. I didn’t know what he was thinking. We were friends, but in reality, we’d only know each other a short while.

Law usually shot out of the school’s rear double doors marked GYMNASIUM—ATHLETE’S ENTRANCE as soon as practice was over, but after ten minutes, I wondered what was keeping him. I hadn’t seen him at lunch, because I had skipped lunch and spent the period in the library. I wasn’t likely to run into any football players or fans there.

Law and I usually stopped for double-dog foot longs and thirty-two ounce shakes. I was beginning to get hungry, weak, and a little shaky, so when Law didn’t show, I headed for Benny’s alone. A condition I might as well get used to.

As I waited at the light at Tenth and Dole, I scrolled through the text messages on my el cheapo phone. Nothing but venom and filth. The messages called me every insulting name in the book, and some not in any book. I could have got some of them in trouble for making physical threats, but I decided to let it slide in the hope tempers would cool. Besides, I didn’t want to add more fuel to the fire. I wasn’t afraid of them, but I wasn’t stupid either. I wasn’t going to let them get me in some out-of-the-way place where I’d be outnumbered.

I thought Law might have sent one. Nothing. I checked my missed-call log and then my voice messages. Nothing but more insults and threats. Another caller’s messages were conspicuously absent. Ashley—my long-distance girlfriend—and I texted each other every day and talked for an hour or so most nights, longer on weekend afternoons.

Ashley and I had dated for eight months before Dad moved the family to Branard. After Dad made his announcement, Ash and I spent a lot of time talking about our options. I thought it might be simplest for us to break up and still date whenever I got back to Houston, but Ashley began crying. She looked so hurt, I’d agreed to try her alternative plan, the long-distance dating thing.

The plan? I’d drive back to Houston every other Saturday unless we made the state playoffs. If I had a playoff game on Saturday, I’d drive back after church on Sunday and stay a few hours before heading back to Branard. We also planned to spend Thanksgiving holidays together. The whole thing proved a lot harder than I had first thought, and I hadn’t been able to make it back to Houston as often as I had planned.

Maybe Law decided to do the smart thing, cut his losses, and dump me. As I was pulling into Benny’s, my phone played the text-message ringtone. It was a text from Ashley. We nd 2 tlk. Not text. Phone 911.

I’ve always been clueless when it comes to texting in code, but I knew “Nd 2 tlk” meant “need to talk.” Ah, the dreaded old “We need to talk” bit. Even I knew when your girlfriend said, “We need to talk,” she meant, “I want to break up.”

Screw it. I’m not really in the mood for another kick in the gut. Let her squirm awhile.

I pulled into Benny’s parking lot and found a parking spot in the shade under the metal awning. I thought Law might show up later with some lame excuse for not meeting me after practice, but when I reached the door, I saw a table of my teammates at the big front corner booth by the window, and Law was with them. I fought back a wave of anger, spun around, and walked back to my truck.

I pulled around to the drive-through window. I wasn’t about to let those clunks stand between me and my most basic needs, food and pretty girls. Lock up your daughters, Branard. Captain Cujo is single and on the prowl.

“What can I get cha?” It was lovely Lisa Brazo. My mind blanked. She had the prettiest eyes I’d ever seen. They were a mix of deep green and brown with an iridescent quality. I studied her face. Gorgeous, and that was a word I almost never used, but it fit. Her face was perfection, oval and soft, young and innocent, but with full sensual lips shaped into a permanent slight shy smile.

“What would you like to order?” She spoke louder, mistakenly attributing my mute condition to not hearing her the first time.

“Uh, ah, I’ll have a medium chocolate shake and a banana,” I said.

“A banana what?”

“Just a banana. You know, still in the peel.”

She wrinkled her nose and asked, “On the side, and not in the shake, right?”

“Right.” I chuckled. This girl has a sense of humor. I had only seen her from midchest up, but I already knew the rest of her would be sheer perfection too.

“I don’t know if I can sell a banana like that. I’ll need to check with someone.”

She smiled at me over her shoulder as she disappeared around the soda machine. I didn’t know if it was a nice-to-meet-you smile, or a we-must-humor-the-mentally-ill smile. When she returned to the window she said, “Seriously, I could slice the banana and put in the shake if you like?”

I almost blurted out, “Why would I want that?” but didn’t.

“My manager said jocks sometimes do that.”

“No, just give it to me whole and unpeeled,” I replied.

“The shake or the banana?” Another big beautiful smile.

The girl is flirting with me. This is promising.

I gave her my very best smile, a bit of innocent boyish grin, with a dash of mischief, and a pinch of bad boy thrown in. I said, “You’re Lisa Brazo, aren’t you?”

“Do I know you?” Her smile began to fade.

“My name is Todd. I moved here a couple of months ago,” I told her.

She nodded an Oh.

“My friend, Law Stefanac, told me who you were.” I didn’t want her to think I was a stalker.

Her reply surprised me. “Are you a jock?”

Oh no, she hates jocks.

“Does it matter?” I asked.

“Not really. It’s just the banana thing.” Her smile was all but gone. “That’ll be five forty.”

Damn the torpedoes and full speed ahead!

I handed her a five and a one and motioned for her to keep the change.

When she gave me my order, I said, “Look, I was wondering… How would you like to hang out sometime, maybe see a movie, go bowling, or something?”

Bowling? I don’t bowl. Oh no, redneck-itis is catching.

Lisa wrinkled her brow and tilted her head the way people do when they are puzzled. After a brief but awkward silence, she said, “I’m sorry. I don’t really know you,” and slid the order window shut.

Ssssssss-boom! Shot down. I was busy preparing for a wallow in self-pity when the guy in the car behind me laid in on his horn. I saw him waving frantically in my side-view mirror. He must have been a french-fry addict in desperate need of a fix. I rammed the truck in gear and squealed the tires as I took off. It was either that, or me storming back to the guy’s car, snatching him out through

the window, and force-feeding him his horn, steering wheel and all.

I hated my life. My best friend had abandoned me, the whole town wanted to burn me at the stake, my girl had just dumped me, and the lovely Lisa Brazo shot me down. Normally, I was a pretty positive guy, and until the past few days, a happy one. Now, I was the world’s biggest loser.

I was glad we had a short school week, just one more day before Thanksgiving vacation. If I could make it through one more day, I’d have a long weekend, four days to let things settle back to normal. The question was, exactly what would the new normal look like?

»»•««

Mom was already in bed when I got home at six thirty, and Dad was in the kitchen frying breaded pork chops and eggs. The swollen bags under his eyes could have held a week’s worth of groceries, and no two hairs on his head lay in the same direction.

I asked, “Dad, what’s wrong? You look like you’ve been through the grinder.”

He shook his head and dismissed my question with a wave of his hand.

I wouldn’t let it go. “Is Mom sick or something?”

He looked over his shoulder and smiled a hesitant smile. “Oh, hi, Son. I’m glad you’re home. Could you finish these eggs while I go check on her?” He scurried down the hall toward their bedroom.

I looked at the mess on the kitchen counter and knew Mom hadn’t been there. She called Dad the kitchen tsunami. “Every time you cook,” she’d say, “you get more food on the counter and floor than you do on the plates.”

When Dad emerged from their bedroom he said, “Try to be quiet. She’s trying to sleep.”

After dinner, I eased the bedroom door open and peeked in on Mom. She was awake. “I’m sorry I didn’t come see you sooner, but I was cleaning up Dad’s mess in the kitchen.”

“You don’t have any room to talk, young man. You are just as bad.” Her voice was weak, and she winced as she spoke.

I told her, “Yes, but we creative types are born free spirits. You wouldn’t want to stifle our chimera-like creativity, now would you?” She was always pleased when I showed off a new vocabulary word like chimera, so I always tried to work my latest lingual accretion into the conversation. She’d signed my phone up for one of those “build-your-vocabulary” texting services. I guess she was afraid my new friends would have me talking like a hillbilly if she didn’t intervene. She needn’t worry anymore. Chances were no one in Branard would ever speak to me again.

Half the Distance

Half the Distance